published on World Design Capital Helsinki April 26, 2012

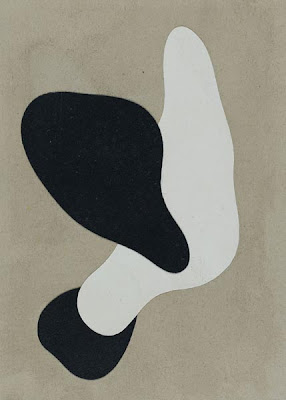

| Two men and their manifest of the naive form. It may not appear as huge surprise that both men were continuously experimenting with form and composition. Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto, the Finnish architect, and Hans Arp, the German- French sculptor and artist, were likewise determined to produce aesthetics by the nature of their profession. While being stylistically defined by different cultural and personal backgrounds, artistic and commercial motivations as well as the creative schools of their time, they eventually met in rounded, simplistic shapes – with a hint of naivety and humoristic directness. Hans Arp is considered one of the leading sculptors of the classical modern period. Trained in art in Weimar and Paris, he co-created the art movement “Moderner Bund” in 1911 through which he met Wassily Kandinsky and got in touch with the art group “Der Blaue Reiter” – acquaintances that led to a milestone in cultural history: In 1916, together with Hugo Ball and others, Hans Arp co-founded the Cabaret Voltaire, and thus became part of the first manifestation of Dada. Subsequently, he emancipated himself as one of the major protagonists of French Surrealism, alongside the likes of Andre Breton and Max Ernst. Throughout his work, the organic, human and animalistic re-appeared as core motifs, while Arp referred to his use of natural forms as “act of randomness” – an approach that already indicates his impish-childish personality. And then, there is Alvar Aalto, the renowned Finnish architect and product designer. A man who persistently referred to his creations as a ‘total work of art’: a living symbiosis of architecture and interior, including furniture design. His milestone achievements equally inherit the zeitgeist of their time, ranging from Nordic Classicism to International Modernism to an organic, modernist style. His re-orientation during an ‘Organic Period’ within the 1940s implicated a shift of consciousness and formal identity. Aalto used small-scale paintings as sculptural experiments during the architectural design process to be later translated into real- life executions. In the context of form, Alvar Aalto stated: ‘Form is a mystery that defies description but brings people pleasure.’ So when did the aesthetic identities of these two front men of world design meet? When did this merge happen? When did their body of work diffuse into each other like the liquid forms they produce? The answer, indeed, is easily given. The climax of ‘Organic Modernism’ can be allocated to an exact time and place: the creation of the Savoy Vase in 1936. The story began during the early 1930s. As member of the Congres Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne, Aalto attended the forth congress in Athens in 1933 where he established a close friendship with László Moholy-Nagy. | From this moment on, his use of forms was strongly influenced by the Bauhaus design school and the formal universe of post-cubist abstract art. His 'organic' proposition seemed synchronized with the aesthetics created by artists such as Juan Miró and, most strikingly, Hans Arp. The intense connection between international abstract art and the forms of Aalto’s Savoy vase reveals itself further, when having a closer look at the development process. The vase was part of Alvar Aalto’s winning proposal for the 1936 design competition organized by Finland's glassworks Karhula and Iittala. Aalto delivered a sequence of sketchy, almost casual drawings, some of them reminiscent of cubist still-life collages, and gave his entry the Swedish code name of ‘Eskimoerindens Skinnbuxa’ (Eskimo Woman's Leather Pants). His series was acknowledged and proclaimed suitable for being presented at the Paris World’s Fair one year after. Aalto’s approach did not only recall his very own architectural drawing technique but also reflect the ironic nonsense-qualities of Dada and Surrealism. And, when examining the Savoy vase drawings closely, they become remarkably familiar with the naive relief collages of Hans Arp. Exploring the Surrealist principle of a dialectic relationship between formal development and thematic association, the singular fragments suddenly refer to well-known forms of nature – but in such a simplistic way that interpretations become absurd as such. This concept of multi-meaning and multi-messaging, as a result, unites Hans Arp and Alvar Aalto. The multiple interpretations of Alvar Aalto’s Savoy vase impressively demonstrate a ‘confusing state of flux’. While Arp’s tableaus are reminiscent of a plate with vegetables or ‘funny’ peep show scenes, the undulating forms of Aalto’s iconic vase redraw the characteristic shapes of the Finnish landscape with its myriads of lakes. The sinuous lines are also said to quote the base of a tree where roots branch out. Or, furthermore, the formless nature of the fluids they contain. Aalto himself puts it more direct: The lines of the vase were prompted by the captivating shape of a puddle. While interpretations tend to super-stage his design philosophy, Aalto himself prefers to relativise them and confront the audience with a more demure, yet capricious view: Puddles, not lakes. Comparing and reviewing the work of Hans Arp and Alvar Aalto side to side, one feels naturally drawn to one conclusion: When the Savoy vase was shaped through the masterful hand drawings of Alvar Aalto, Modernism became Surrealism became Modernism. And a piece of ‘world design’ was created, fundamentally and iconic. |